Political causes, traffic pauses

March 1, 2019

It was 2:15 p.m. It would only take my dad and me 15 minutes to drive from the Mission District to the college admissions office near Market Street in San Francisco where my 3 p.m. interview would take place. There was plenty of time. Or so I thought.

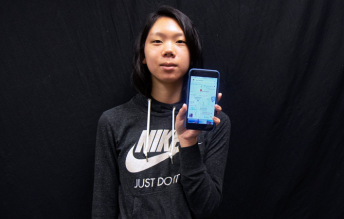

2:30 p.m. The line of cars had barely moved. I craned my neck to see what was going on, then frowned as I saw a police officer directing cars away from the street we needed to turn onto. I searched Google Maps for alternate routes, but the directions didn’t make any sense: no matter how often I refreshed the application, it kept pointing me back to the street that was obviously closed. Frustrated, I watched my estimated arrival time creep past 3 p.m. Knowing it would be faster than driving, I hopped out of the car and started walking to my interview.

2:57 p.m. I was out of breath from 30 minutes of panicked walking and running. Just a few feet away from me, a group of protestors holding signs with messages like “I am the pro-life generation” was walking down Market Street, an explanation for the street closures and heavy traffic.

Due to the Walk for Life, an anti-abortion march which draws more than 50,000 people to San Francisco each year, numerous streets in the city were partially closed on the afternoon of Jan. 26, just a week after the Women’s March. Street closures included parts of Howard Street and Market Street, major streets of the city that I needed to get from the Mission to my interview location.

Although inconvenient, such street closures are a necessity for the safety of protestors. However, to reduce the chaos during large events such as protests, parades or festivals, large cities like San Francisco must develop better systems of communication with residents, visitors and large web mapping systems. Luckily, I made it on time to my interview, but what about those who couldn’t just jump out of their cars? Or those who had much further destinations?

That day, when my car reached the intersection where the street was closed, there was only one police officer preventing drivers from turning onto the street and a sign stating that the street was closed; nothing provided suggestions for alternate routes. A simple solution to many drivers’ headaches in the event of street closures would be for the city to put up signs indicating possible detours.

Additionally, until I was met face to face with the protestors, I had no idea about the reason behind all the chaos. With the advanced technology at our fingertips today, cities should develop alerts that can be sent to smartphones of users within city boundaries when a disruptive event is happening. Such alerts would detail issues residents and visitors might face, such as traffic and street closures, and inform them on how to work around these situations.

Similarly, cities must improve communication with web mapping systems. Even after I had driven past the original directions, Google Maps kept redirecting me to the street that was closed. Silicon Valley is a hub of innovation, so I’m confident that cities and web mapping services here can develop better ways to communicate on events that might cause street closures or affect traffic and driving routes.

Although marches are a key aspect of American political life, it is also important for cities to realize that their residents’ lives can be significantly impacted by such demonstrations. I’ve always wholeheartedly supported the freedom of assembly, but it only took me 30 nerve-wracking minutes to recognize the necessity of ways to streamline traffic and improve communication in the event of protests and other large events. By developing better systems of communication with residents and visitors, in addition to working with large web mapping services like Google Maps, cities can ensure that residents’ lives flow smoothly while protestors exercise their right to assemble.