Editorial: Redefining American literature

February 1, 2019

Being American in the 17th century meant being Caucasian, and being an American author usually meant being a white male; however, the past four centuries of America’s existence have undoubtedly altered what it means to be American. A glance at the country’s culture in recent years clearly demonstrates this: tremendous efforts have been made toward women’s rights, LGBTQ+ rights and racial equality, with the Women’s March, Pride Month and #BlackLivesMatter movement.

Despite this, the changing American social fabric has been minimally reflected in the curricula of American Literature and AP English Language and Composition (APLAC), even though the FUHSD defines American literature classes as “a chronological or thematic study of American literature, its literary periods and major writing,” “encouraging wider reading including classics by American authors” and states that “[APLAC] uses a survey of American literature and writing.”

Decisions regarding the content taught in each classroom are largely made at a state or local level; at Lynbrook, English course curricula and the master list of literature for all classes are decided by the English department. Junior year core texts, which all American Literature and APLAC teachers must teach, include “The Scarlet Letter,” “The Great Gatsby” and “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.” Teachers are free to choose their additional pieces of literature, as long as they contribute to the courses’ main objectives of students becoming familiar with the American literary tradition and can connect it with the nation’s history; however, the current American pieces chosen by teachers do not do America’s traditions and history justice.

“One of the problems is that many of the big foundational works were written by white men,” said Robert Richmond, English Department Lead and APLAC teacher. “But there’s also a very rich and wonderful collection of contributions by women and people of color. We have to try to make room for that.”

Additionally, the definition of American authors includes a vast range of individuals other than white males.

“A lot of times we read works by the same authors, who are usually a part of European culture, and it’s important to understand other worlds’ cultures because they are just as important,” said sophomore Helen Hu.

Representing American literature with a majority of works by white males would not only be historically inaccurate, but it would also be an unjust neglect of the various ethnic groups and minorities that contribute to American culture. Students must be exposed to a wider range of experiences, as not doing so would be failing to recognize that America’s history was forged by a plethora of ethnic groups, as opposed to just one.

“[American literature] should be representative of the different cultures that make up America, which is a melting pot,” said American Literature teacher Jessica Dunlap, “Ideally, we would be able to see the whole spectrum of what it means to be American, to see the variation in the American experience.”

Individual teachers at Lynbrook have already made efforts to diversify courses, despite the possible challenges in expanding them. It can be difficult to find texts that provide both broad cultural experiences while balancing having appropriate content for high school readers and engaging students in deep discussion.

“We think about ways to change up the curriculum, but the problem is finding works that are more representative of the diversity in our country that are meaty enough and appropriate for classroom discussion,” Dunlap said.

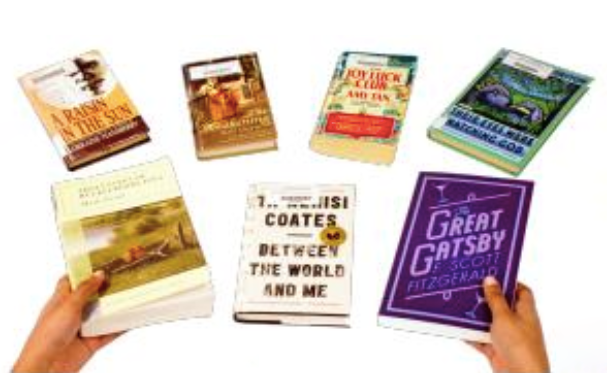

World Literature and European Literature teacher Kristy Harlin has included “In the Time of the Butterflies” by Julia Alvarez in her lessons for several years, and Richmond and Dunlap have included “A Raisin in the Sun” by Lorraine Hansberry. Additionally, several American Literature and APLAC classes include a supplemental reading project in which students choose an American novel from a comprehensive, diverse list. Possible works by immigrant authors include “Their Eyes Were Watching God” by Zora Neale Hurston, “The Good Earth” by Pearl S. Buck and “The Joy Luck Club” by Amy Tan. Despite current efforts, more must be done to improve on the current lack of diversity.

“To me, what we have still doesn’t seem adequate,” Richmond said. “We need to look at the whole curriculum.”

While discussion of the issue at hand has begun in the FUHSD and across America, greater efforts at district and state levels ought to be made to align the literature American students read with the diversity of America. Maintaining the 17th century definition of “American” is a failure to accurately represent the America of today. If an objective of studying American literature is to connect it to American history, it must done with both accuracy and sensitivity.