Addressing racial injustice with reparations

Graphic illustrations by Deeksha Raj and Neha Ayyer

After June 1, city officials have until Sept. 19 to accept the final report, which will then open the pathway for supervisors on the board to develop plans toward funding chosen recommendations.

April 10, 2023

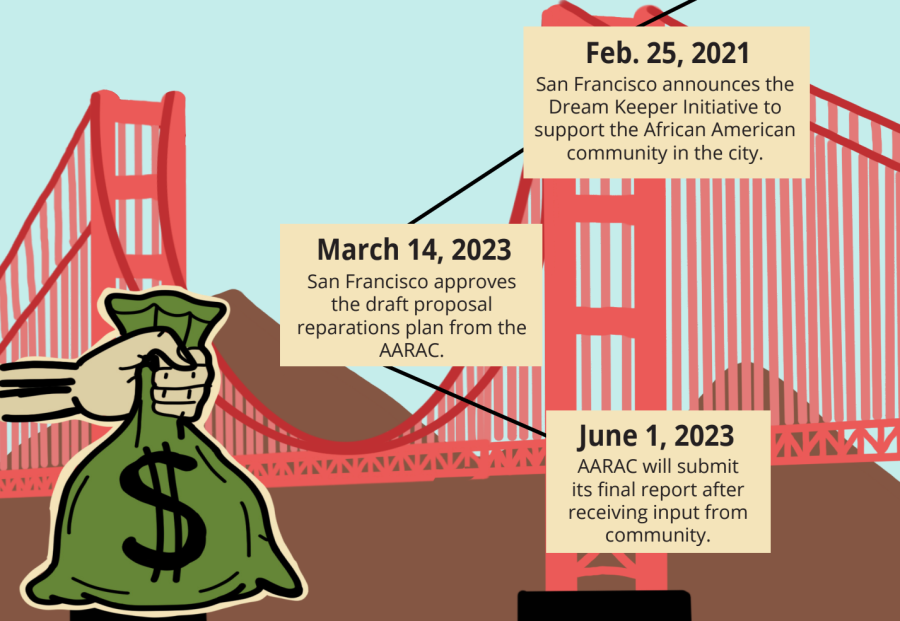

On March 14, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors unanimously approved a draft plan for reparations for the African American community, as proposed by the San Francisco African American Reparations Advisory Committee. Reparations refer to compensation given to individuals or communities that have suffered from injustices as a way to acknowledge and recompense past wrongdoings. Although the approval does not enact any of the recommendations and merely indicates the board’s willingness to take the next step toward redress, debates have sparked over the best manner in which to address the city’s historical racial discrimination and implementation of reparations as a whole.

AARAC, the committee behind the proposal, was formed in 2020 under the backdrop of the Black Lives Matter movement and in light of acts of racial violence such as the death of George Floyd. The objectives of AARAC’s 111 recommendations encompass four categories: health, economic empowerment, education and policy.

The committee first examined the city’s roots in racial inequality to determine proper reparations. Although San Francisco was never involved in chattel slavery, it has contributed to systemic discrimination in other ways. Its 1852 Fugitive Slave Act clashed with the California constitution’s anti-slavery clause by allowing the deportation of formerly enslaved African Americans brought into the free state. During the gold rush of the 1850s, Southern slave owners brought slaves to San Francisco in search of riches, and many slaves were employed to build California’s railroads. Disenfranchisement and school segregation lasted well into the 1870s. San Francisco was also the home to California’s first chapter of the domestic terrorist group, the Ku Klux Klan.

The remnants of Jim Crow laws, gentrification, redlining and housing discrimination led to an increasing racial wealth gap and decreasing Black population, marking San Francisco as currently having one of the lowest Black populations among the largest 14 cities in the nation. California’s 1945 Community Redevelopment Act allowed for the destruction of the Fillmore neighborhood, once the cultural heart of San Francisco’s African American community, and landowners have been known to engage in restrictive covenants to prevent certain ethnicities from purchasing homes.

“I have experienced evictions due to capitalist purposes,” AARAC member Gloria Berry said. “My whole apartment building of six Black families were all evicted to convert those units to condominiums. We were not lazy, not a blight — my father drove the cable car for 25 years and my mother was a secretary for the federal government.”

The legacy of these racial barriers is still felt today. A recent report from the National Bureau of Economic Research has shown that San Francisco is particularly prone to discrimination against African American renters. Black infants in San Francisco have a mortality rate four times that of white infants, and Black mothers also face increased mortality rates from childbirth complications.

Examples of reparations to address these and similar problems across the nation have been mostly executed in the past few years, such as California being the first state with an official reparations commission in 2020 and Evanston, IL being the first city to implement reparations in 2021. San Francisco’s new draft plan falls in line with the motive behind recent efforts, but aims to create greater change through bold measures.

Eligibility for the reparations included in the bill requires the individual to have identified as an African American for at least 10 years and be over the age of 18, as well as meet specific requirements regarding descendants in specific time periods in order to identify families who have been affected by discrimination. Under each objective, the bill is divided into sub-categories of proposed actions. Along with issuing a formal apology and promise to make investments in Black communities, an Office of Reparations will also be established to ensure the progress of the programs. A committee of community stakeholders will be created and funded to help implement policy initiatives.

With financial reparations available to people who qualify, it is likely each person will receive some monetary compensation in addition to other supplements such as debt forgiveness, tax credits and an enhanced bank framework that ensures access to credit and loans. Home ownership would also be made more attainable with new funding loan programs, covering monthly living expenses, subsidizing mortgage loans and offering grants for home maintenance. Furthermore, public housing units would be converted into condominiums with a $1 buy-in. These reparations would help temporarily mend the financial and living issues which stem from racism.

However, some are also concerned about the reparations not addressing the problem at its root.

“I’m more interested in solving a long-term problem,” history teacher Jeffrey Bale said. “If nothing is structurally changed, then what’s the point? Paying off millions of dollars does not wipe our hands clean of the whole incident.”

While promising bright prospects for those who qualify for reparations, critics have argued otherwise. One argument is that because California was never part of chattel slavery in the U.S. nor endorsed it, it would be unfair to the taxpayers who would have to handle the cost of systemic racism in government policies. Stanford University’s Hoover Institution estimated that each non-Black family — which includes immigrants in San Francisco — would pay $600,000 in taxes until the reparations are accommodated. Pew Research Center showed that 68% of US respondents opposed the reparations. Among the people surveyed, 80% of Black people surveyed supported the reparations while 90% of Republicans opposed.

“We definitely need to have more discussion on ways monetary compensation could be done,” Berry said. “But that’s where creativity comes in. It could be through installments, or prioritizing those with unstable living situations; we need the mayor and other officials to work with us to find ways it can happen.”

Many activists also argue that the bill raises unrealistic hope for the Black community. Although progressive plans are being approved, it is uncertain how SF plans on funding the reparations.

The AARAC is continuing its monthly meetings at San Francisco City Hall until June 1, when it will submit its final report. Meanwhile, the city is also in the process of potentially establishing an Office of Reparations. After June 1, city officials have until Sept. 19 to accept the final report, which will then open the pathway for supervisors on the board to develop plans toward funding chosen recommendations.

“I would define the success of the plan as meaning that our little boys and girls will feel loved,” Berry said. “That they will feel like they’re human.”