Beneath the surface of Calif.’s water infrastructure crisis

Graphic illustrations by Sarah Zhang and Daeun Chung

The water crisis in California is a complex and multifaceted issue that requires immediate action from policymakers, businesses and individuals alike.

April 10, 2023

Trillions of gallons of precipitation have poured down on California this winter, breaking the state’s driest recorded three years. However, most of the water has returned to the ocean, rather than replenishing California’s under-supplied water system. The problem lies within ill-prepared water infrastructure that fails to capture and store stormwater in aquifers and reservoirs.

California’s existing water infrastructure stores water in large reservoirs and underground aquifers — an overlooked source that contributes to the majority of the state’s drinking water. According to Stanford’s Woods Institute for the Environment, 50 million acre-feet of storage are available in reservoirs compared to between 850 million and 1.3 billion acre-feet of storage in aquifers and other groundwater sources. However, for the past 20 years, the available water stored in the aquifers is on a decline. The need from major consumers of water, such as the Central Valley’s agriculture economy, has been growing faster than aquifers can be replenished. Due to tight regulations on who can take water from rivers, aquifers are without a stable supply to replenish reserves. While this achieves its goal of equal access during dry spells when water is highly contested, the regulation is unable to adjust during a large influx of water in rivers during storms.

“To do more for all sectors in the state, it is all about if we can store water more effectively,” said Bruce Cain, Professor of Political Science at Stanford University and Director of the Bill Lane Center for the American West. “The floods indicate the problem that we get a ton of water sometimes and no water most of the time, so we have to make sure that we save water to use when we do not have water.”

Due to the lack of supply from aquifers, reservoirs now account for 60% of the state’s water supply and have become the focus for legislators and residents alike. In Northern California, reservoirs were replenished due to the recent storms but the water was drained into the ocean to prevent flooding, leading to public outrage. In contrast, reservoirs in Southern California had trouble reaching desired levels, but all major reservoirs in the state are at least at 80% capacity, a major sign of progress in a drought-ridden state.

“To protect areas downstream from the dams and reservoirs, the state will be drawing water out a little bit so there’s room there to store that water,” said David Freyberg, Associate Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Stanford University and Senior Fellow at the Woods Institute for the Environment. “The goal is when the snow melts, the reservoir will be just filled up to the tip-top so there’s lots of water there for the dry summer that’s coming.”

Yet, slow progress hampers the increase of reservoirs that many believe are needed to adapt to future storms. The Sites Reservoir to be built on the Sacramento River, for instance, has been planned for nearly four decades but construction kickoff is planned for 2024 and is likely to be delayed due to weak public support. Difficulty acquiring permits in consideration of environmental concerns such as fishing health has also stood in the way. Legislators have balked at the slow pace of reservoir construction, believing it to be the key to maintaining a stable water supply.

“The bottom line is that our old system of dams and reservoirs are getting old and their capacity to hold water is decreasing because many of them have silt or other damage to them,” Cain said. “It is hard to build new dams and reservoirs, partly because there aren’t as many good places to build them, but also we are more conscious than we were in the early 20th century of the ecological effects of building more.”

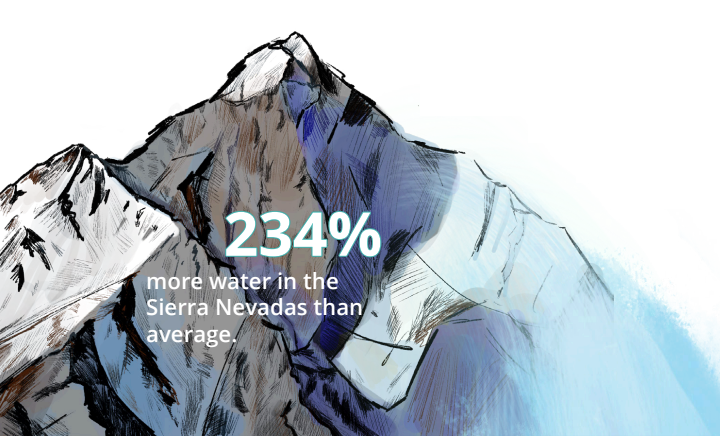

Aside from physical infrastructure, climate patterns and climate change over the years have contributed to inconsistent snow and rainfall, from the Sierras to the Central Valley. Rising summer temperatures have resulted in dry soil and arid basins, while the warmth carries into the winter and results in even more intense storms. Since the fall of 2022, cities have received anywhere from 10-30 inches of rain. The last time the state saw precipitation at these record levels was the El Nino winter of 1997 to 1998. These erratic patterns will have long-term consequences on California’s water supply as it becomes increasingly difficult to predict and plan for droughts and other natural disasters, which in turn can have a ripple effect on the state’s economy, public health, and overall quality of life.

“The storms also indicate another problem of resilience,” Cain said. “If we are going to essentially have a system that stores water successfully, we have to protect it from increasingly harsh weather.”

While more precipitation replenishes water supplies, the storms have been particularly threatening. On Jan. 4, Governor Gavin Newsom declared a state of emergency to keep the state on high alert for dangerous storms. A week later, President Joe Biden granted federal disaster relief for many California counties impacted by flooding and storms. The flooding has revived long-dormant lakes such as the Tulare Lake in the San Joaquin Valley; nevertheless, other counties worry if flood levees can withstand the intense flooding. In the San Bernardino mountains, death tolls are rising from blizzards that dumped snow on residents, trapping them in their homes.

“Levee failures are examples of the hazards of flooding conditions,” Freyberg said, “It’s just part of the ecosystem processes but we put a lot of infrastructure, homes, businesses, roads and power lines adjacent to these rivers.”

In August 2022, Newsom issued a new California water supply strategy: “Adapting to a Hotter, Drier Future,” which targets water supply by expanding reservoirs, replenishing groundwater and increasing stormwater capture. This plan continues a three-year legacy of legislation for improving water infrastructure and management. California’s 2022-23 allocation of $2.8 billion toward drought relief, environmental protection and water conservation is on top of a $5.2 billion investment into water infrastructure made in 2019. Newsom is proposing an additional $202 million and $125 million for flood and drought protection, respectively, for the 2023-24 state budget as well. Furthermore, in response to this season’s flooding, Newsom issued an executive order on March 10, relaxing the regulations for capturing floodwater without permits.

“One thing we haven’t been able to do very effectively is to have a statewide water plan that systematically takes all the various trade-offs and the different ways that we could handle water and says what’s best for the state as a whole,” Cain said.

In response to the recent water crisis, new technologies to conserve and recycle water are gaining popularity. For example, research surrounding how to treat wastewater and stormwater by the biofiltration of contaminants has been at the forefront. The use of desalination plants has also become increasingly popular in California, where salt and other minerals are removed from seawater to supply drinkable water. Other examples of technologies include using satellites to track agricultural water usage, cloud-seeding drones that zap clouds with currents to induce rain and micro or drip irrigation to deliver water to the roots of plants.

“Most people are not yet very comfortable with recycled water but it’s gaining traction,” sophomore Daphne Zhu said. “As the technology becomes more advanced, it could potentially become a bigger part of our water supply in the future.”

Today, the water crisis in California is a complex and multifaceted issue that requires immediate action from policymakers, businesses and individuals alike. With declining aquifer supplies, aging reservoirs, inconsistent rainfall patterns and the impacts of climate change, the state’s water supplies are constantly under immense pressure. While the problem is difficult to condense to a few solutions, the implementation of innovative technologies, policy reforms and sustainable practices gives California a chance toward a more resilient water future.