Summer Reflections: Lessons learned in a foreign classroom

Taking inspiration from the children of Nepal

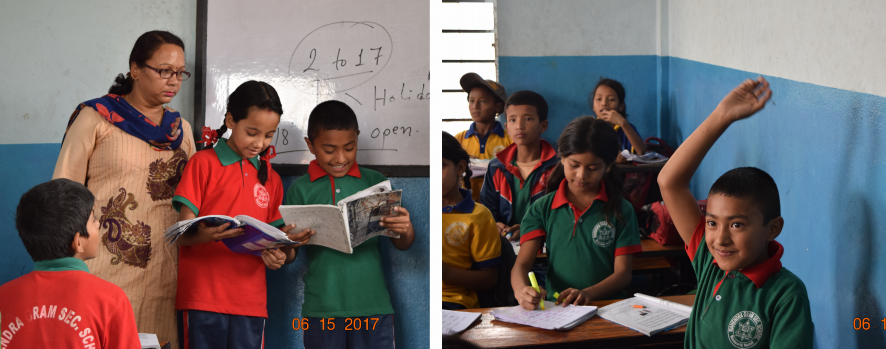

Four rows of tables, attached to well-worn benches, fill the small room, no bigger than my bedroom. The walls, once light green, are peeled and fading, covered with dirt and vestiges of adhesive tape. The only source of light comes from the open windows on two sides of the room, a light breeze drifting through the wooden slats and ruffling papers. I took in all of this as I stepped into a third grade English class at Shree Mahendra Gram Secondary School.

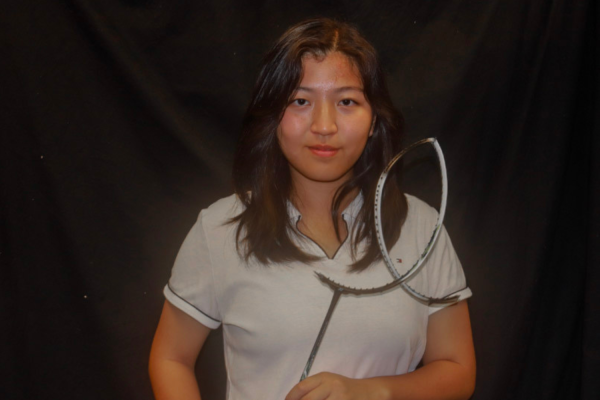

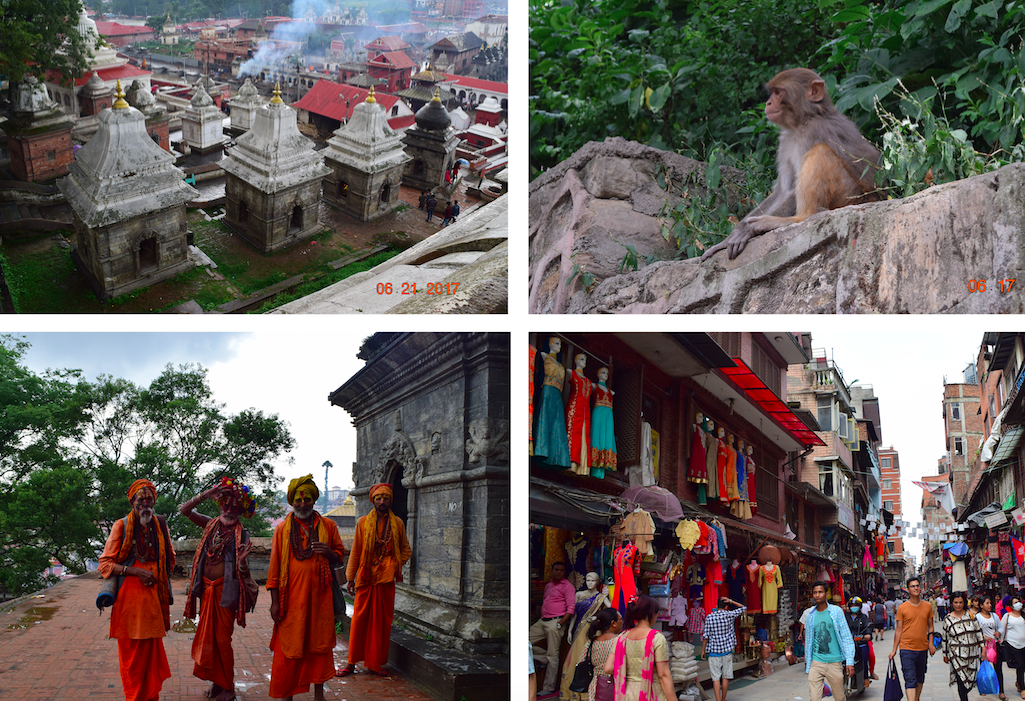

This summer, I traveled to Kathmandu, the capital of Nepal, for a service trip. Along with around thirty other students, I cleaned and painted the walls of a small school. Our goal was simply to finish the job in a little less than two weeks, but the trip entailed much more than that. Besides painting walls, I enjoyed the colorful streets, visited a national relic, the Swayambhunath Stupa, or Monkey Temple, and learned about Nepal’s unique culture.

Most importantly, I met many people, namely the youth of Kathmandu. Despite my limited time in Nepal, and language barriers, my interactions with these people have been the most eye-opening aspect of my Nepal experience.

When we first arrived at Mahendra Gram, the students gathered in the school’s small courtyard. Many had flowers in hand, which they handed to us, cheering, as we walked through the crowd. They had never seen anyone of a different country, with iPhones and clothes from Nike or Adidas. Like any other children, they laughed and chased each other around. When the bell rang, they were reluctant to go to class, peering curiously over the railings.

I couldn’t stop smiling the entire time.

In one third grade English class of around twenty students, the teacher led the class in reading passages from their books. As a class, their voices rang loudly throughout the small room, but they were shy when asked to individually introduce themselves. The entire class shouted answers eagerly when I asked them questions from the book, and were not the least bit discouraged when they got an answer wrong. Later, when I sat down to talk to them individually, they gathered around, clamoring to show me how to write their names in English. Although I’d only spent half an hour with these children, I didn’t want to leave when we started painting again.

The principal of Mahendra Gram, Bharat BabuKhanal, was extremely dedicated to both the education and welfare of the children in his school. He was friendly and open to the students, taking time to connect with each and every one of them.

“Mostly I want to go to the lower classes and sing English songs,” BabuKhanal said. “After singing some songs, I want to ask about their problems, if they have any. They may be hesitant to tell everything to some of the teachers, but they never hesitate to tell anything to me. I’m solely responsible for each and every child’s problems and their improvement.”

By the time we finished working at the end of the trip, the walls of Mahendra Gram were covered with a fresh layer of paint. Two murals decorated the landings on a staircase, and even ceilings were clean and white. Despite this improvement, the floors were still dirty, and chunks of cement were missing from the stairs. The classrooms still did not have proper lighting, and there were no playgrounds, just a small courtyard and a few table tennis balls.

Comparing these conditions to the brightly lit, carpeted classrooms I was familiar with, I felt a surge of gratitude. I felt proud of what we accomplished, but I still couldn’t imagine going to school here. Despite their environment, the children had an innate will to learn. However, as they grow up and become more aware of their financial, familial and physical situations, they may consider education as less of a priority.

I visited an orphanage during the second week and met a boy around my age. He wore ripped jeans, a worn T-shirt and no shoes. His name was Milan, and he loved dancing, enthusiastically showing me dance moves he’d seen from the internet. His eyes lit up when another student offered to teach him a few chords on the guitar. He later told us that he’d dropped out of school a while ago to find work.

Another girl, also around my age, wanted to be a doctor when she grew up. When I first met her, she was bent over a workbook, writing English letters with a stubby pencil. She didn’t look up until she was finished. Like Milan, she was eager to learn about us and curious about our customs. I thought of all the universities and institutions in the US that trained doctors. To us, these universities may be our goal, but to her, they would only be a dream.

In first world countries such as the US, school has become a fixed portion of one’s life, and we depend on our education in the hopes of leading a better life after graduation. Unfortunately, in Kathmandu, not every child has the opportunity to even graduate middle school. However, even in such developing countries, BabhuKhanal believes that education is the most important thing a child can receive.

“First of all, when people are educated, they can be aware of their situation, the situation of the world, situation of their society, and how to make progress,” BabhuKhanal said. “The second thing [is], after getting educated, it will be easy for them to [find] jobs. In scientific invention, or many other technical lines, education plays a vital role, and we want to cater quality education to our students.”

Outside of a formal education, volunteering work also plays an important role in young people’s lives. Spending two weeks in a foreign country with mosquitos and painting under sweltering heat was not a desirable way to begin my summer vacation, but I don’t regret joining this trip at all. Although we have only changed one small corner of Kathmandu, we were able to create an impact upon the lives of the students there as well as our own.

All photos by Chelsea Li

Chelsea Li is one of the content editors for the Epic this year! She has been on staff since her sophomore year, and it has been a huge part of her...