Screeching brakes cut through the quiet of the night. The ambulance, flashing red and blue with blaring sirens heard from blocks away, tears through the neighborhood. The street is otherwise dark and empty except

Screeching brakes cut through the quiet of the night. The ambulance, flashing red and blue with blaring sirens heard from blocks away, tears through the neighborhood. The street is otherwise dark and empty except

for one house, pulsing with lights, noise and commotion, and in the dark, figures of frantic teenagers try to flee the scene. The possible repercussions? Arrests for underage drinking, overdoses from illegal substances, driving under the influence citations (DUIs) and much more.

Welcome to the darker side of high school parties.

In a setting where drinking, using drugs and other illegal substances can be common practice, the potential consequences can be fatal — from drinking-related car accidents to overdoses, a simple mistake can be devastating. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, about a quarter of car crashes with teenagers involve an underage drunk driver, and teenage alcohol use kills approximately 4,300 people a year. Car crashes related to drugs account for about 18 percent of all motor vehicle deaths.

“Definitely know your limits. Get a designated driver — an Uber or your friend — so you’re not driving,” said senior Aditya Park*. “I tried driving drunk, and [my parents found out]. I felt bad because I had betrayed the wisdom that my parents taught me, to be responsible, and I was really disappointed in myself for making such a stupid mistake. My mom fell on her knees and started crying, and my dad just went silent and went to his room. So I really want to spread awareness about driving home safely because I was careless and irresponsible.”

Such incidents are preventable. Students and parents alike can use safety measures such as confiscating an individual’s car keys to prevent drunk driving, assigning designated drivers who will not drink and drive and limiting the amount of drugs and alcohol an individual intakes. According to a poll conducted by the Epic of 415 Lynbrook students, 61.3 percent of the 80 who have attended a party have had designated drivers for parties, while 48.8 percent of attendees have limited the number of drinks one intakes. Nevertheless, 30 percent have not put any safety measures in place while partying.

“It’s really scary to see some people who are just like, ‘oh, I’m used to it, I can drive high or I can drive drunk.’ Sometimes, a few of my friends and I get really frustrated because it sucks when some of your close friends fall into drug abuse or alcohol addiction and you don’t know how to help them,” said senior Nancy Kumar*. “It’s really frustrating because whatever we say to them just aggravates them, and it’s this fine line between not wanting to just control their lives, but also wanting them to stay healthy.”

Though accounting for safety is more effort on party-goers, it is necessary and pays off in the end, as incidences of hospital visits and DUIs can be avoided. Those who do not drink or use illegal substances may feel left out of the party experience, but they are the ones who ensure their friends are safe.

“It’s kind of like you’re missing out on an inside joke, where they’re all laughing and sharing the same physical feelings, and you know what it feels like, but you’re just not there,” Kumar said. “But afterward, I feel like it’s pretty nice. There have been so many times when I’ve helped people and people have helped me, and I’ve always remembered the people who have helped me and I’m always super grateful for them.”

In a party environment, friends can play both helpful and harmful roles in the safety of their peers. For instance, a teen may experience a moral dilemma when someone experiences a medical emergency at a party where illegal substances are present. If intoxicated teenagers call 911, they will get in trouble for the possession of those substances, but if they do not call emergency services, a person’s life will be put in danger. Though 73 percent of Lynbrook students polled said they would choose to call 911, decisions become often more complex when one is placed in a real-world situation, where judgement may be heavily impaired by alcohol.

“[At one party I was at], two girls in my class got alcohol poisoning, and the ambulances came, but I just ran away,” Park said. “That’s what most people do at parties — everyone just runs away. In this case, the person who rented out the Airbnb [for the party] got into trouble, and the people who got alcohol poisoning because they went to the hospital for underage drinking.”

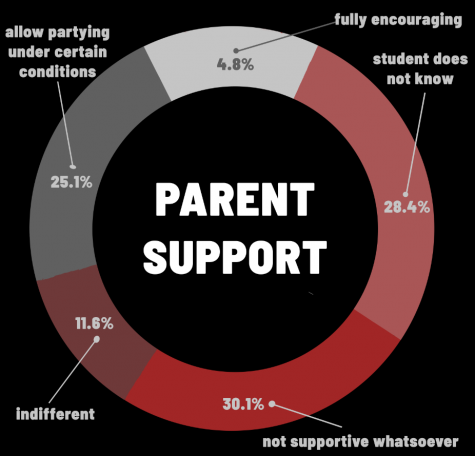

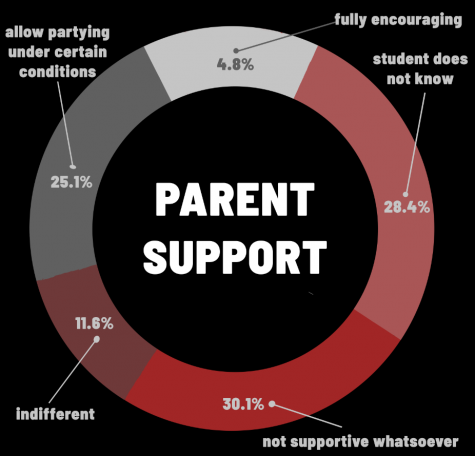

While many parents play minimal roles in their children’s partying, their opinions can both directly and indirectly influence their viewpoints and behavior. Even though some parents are against their child partying, it may be difficult to prevent them from doing so anyway, and they may be even more inclined to party. Some parents may choose to host parties and supply alcohol for teens, while some readily allow them to go out, albeit with certain restrictions. Others may choose to ignore teenagers’ behavior because they want to avoid confrontation, or they do not want to harm their child’s social status.

“I trust my children, and most of the time, I know their friends, so if they let me know in advance where they’re going, who will be there and what kinds of activities they will have, I’m pretty much okay [with their partying],” said Lynbrook parent Kate Lin. “Teenagers don’t need your opinions. They don’t want you to educate them. They just want you to listen. So, I will remind myself to just not talk too much and just show my support and listen with my heart.”

Even though parents may support their children’s partying, laws known as social host ordinances hold adults accountable if they provide alcohol to minors on their property. The law deems it to be the responsibility of adults to ensure that teenagers cannot access alcohol. Therefore, if teenagers are caught drinking underage, property owners — who are oftentimes parents — can be subject to fines up to the thousands, even if they may be unaware of the situation.

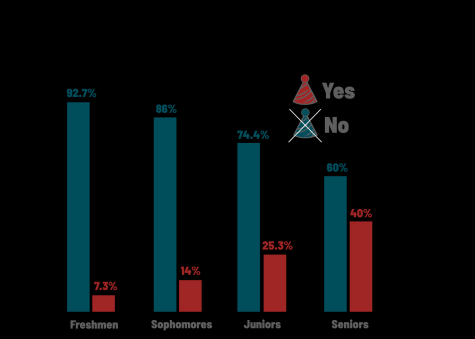

Without parental supervision, partying in college can be drastically different from partying in high school. Parties become both more accessible and prevalent, and college students have more liberty to do what they want, but they also hold more responsibility to watch out for their own and each other’s safety.

Without parental supervision, partying in college can be drastically different from partying in high school. Parties become both more accessible and prevalent, and college students have more liberty to do what they want, but they also hold more responsibility to watch out for their own and each other’s safety.

“In college, most people have a new identity,” said Jessica Peng, Lynbrook Class of 2018 alumnus and current Columbia University freshman. “In high school, I feel like sometimes you fall into the mold that people think you are. In college, people don’t have any identity to follow, so when they are exposed to substances for the first time, they don’t feel a need to act a certain way or hold back, and it becomes easier to abuse them. It’s surprising — you’ll see some of the most innocent, studious kids in high school become completely different in college. Sometimes this is more dangerous because they haven’t had experience with it in the past so they can’t control themselves and end up falling apart. Surround yourself with the right people, because there’s a saying that you become a combination of the six closest people to you.”

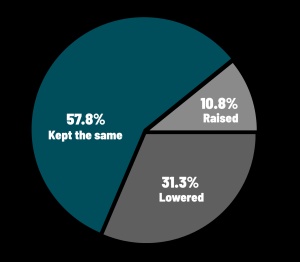

Partying can have negative consequences on teenagers’ health and wellbeing, particularly if it involves alcohol and other illegal substances. Ultimately, tragic consequences result from not only one person’s actions, but also a complicated web of influences. Responsibility cannot be responsibly pinned down to one source in any given situation; it is still necessary to consider the necessity for responsibility itself.

“When we first started drinking, my friends and I agreed that the main reason why we like partying is because every

“When we first started drinking, my friends and I agreed that the main reason why we like partying is because every

Screeching brak

Screeching brak

Without parental supervision, partying in college can be drastically different from partying in high school. Parties become both more accessible and prevalent, and college students have more liberty to do what they want, but they also hold more responsibility to watch out for their own and each other’s safety.

Without parental supervision, partying in college can be drastically different from partying in high school. Parties become both more accessible and prevalent, and college students have more liberty to do what they want, but they also hold more responsibility to watch out for their own and each other’s safety.