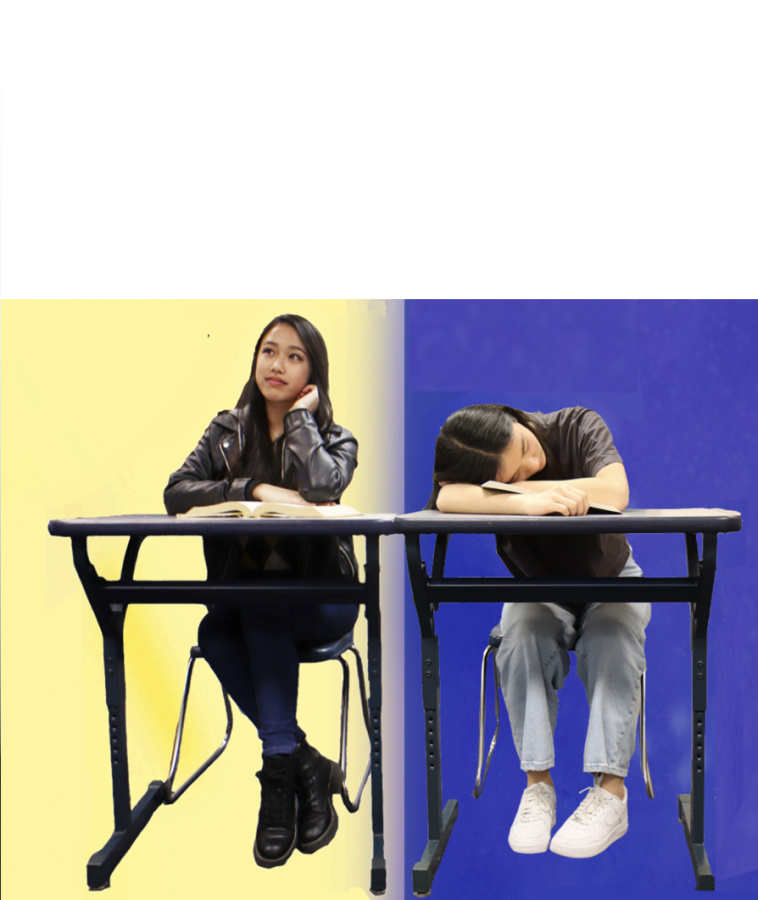

While dreaming is most associated with sleeping, daydreaming is a common phenomenon while one is conscious. A daydream is a series of wandering thoughts or fantasies that occur while a person is awake, usually due to a lack of external stimuli.

Daydreaming is a natural human mechanism that involves imagining places or people, occurring during moments of idleness or when working on tasks, such as doing household chores, commuting or attending a meeting. While daydreaming, humans direct their attention away from external stimuli, allowing mental images, thoughts and scenarios to be pictured. Not only can daydreaming be made up of fictional characters or scenarios, but it can also concern past experiences.

Daydreaming is shown to serve many benefits. This form of mental exercise allows humans to explore creativity, imagination and problem-solving skills, which can help foster innovation, enhance productivity, promote adaptability and encourage critical thinking. Moreover, daydreaming can help process emotions and past experiences, drawing new insights and perspectives that may not have been considered before.

“Daydreaming allows me to drift away from where I am,” sophomore Kashish Mittal said. “It gives me a moment to be by myself and relax.”

However, daydreaming also has its drawbacks, most commonly when it becomes excessive and starts interfering with daily tasks. Maladaptive daydreaming, also known as excessive daydreaming, may lead to decreased productivity and isolation, which diminishes the ability to focus on tasks.

Of 213 Lynbrook students, 58% of respondents voted that they often or always felt fatigued at school. Sleep deprivation, or poor quality sleep, is shown to correlate with daydreaming. A 2014 study conducted by Richard Carciofo et al., found that higher frequencies of mind wandering and daydreaming were associated with poorer sleep quality, particularly with increased sleep latency, night-time disturbance, daytime dysfunction and daytime sleepiness.

“People not getting sufficient hours of sleep, along with possible underlying health conditions, can lead to feeling sleepy in the daytime,” said Cheri Mah, M.D., M.S., sleep physician and Adjunct Lecturer at the Stanford Sleep Medicine Center. “Underlying health conditions including depression, insomnia or sleep-disorders can also result in daytime sleepiness.”

When sleep-deprived, people are more prone to daydreaming as a way to counteract the lack of rest. Not only may sleep deprivation lead to a higher rate of daydreaming, but it may also affect what one daydreams about. Lack of sleep, often associated with increased irritability, can lead to daydreams about negative, worrying scenarios such as catastrophic events and unrealistic expectations, which may lead to obsessive thoughts and self-criticism.

“External stimuli, like physical activity and caffeine, will mask both accumulated sleep debt and daytime sleepiness,” Mah said. “However, it’s just a temporary measure. The sleep debt is still there.”

When people don’t get the amount of sleep their body requires, it can lead to daytime sleepiness. This not only results in increased tiredness, but also leads to microsleeps. Microsleeps are very short periods of sleep, usually lasting only a few seconds.

“Although you may be motivated to stay awake, there are times when tiredness overpowers the motivational control, causing a lapse in attention,” said Erika Yamazaki, Northwestern University neuroscience Ph.D. student. “That can become a microsleep and can be really dangerous when driving.”

Daydreaming increases creativity and imagination, however, it also leads to decreased productivity and attention span. Good quality sleep, sleep that lasts between eight and 10 hours a day, reduces the negative effects of both sleep deprivation and daydreaming. Sleep deprivation is shown to directly influence the likeliness of daydreaming, which decreases productivity. With the same workload left, teenagers are seen prioritizing finishing tasks over sleep, resulting in an endless cycle that leads to tiredness and grogginess.

“Whenever I get less sleep than usual, I always fall asleep in class and feel groggy throughout the next day,” freshman Charlotta Dai said. “But more sleep allows me to have more energy and perform better at school.”